West

Bank Infrastructure Infrastructures,

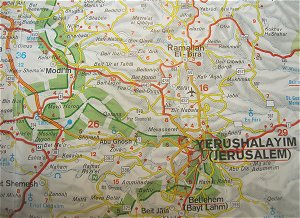

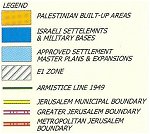

particularly roads are preconditional for spatial and social segregation

on the West Bank. Rob van der Bijl (urban planner) and Liesbeth Sluiter

(photographer) investigate these infrastructures since 2004. They

compile maps, images and histories of the Jerusalem region which

they conceive as a key area within the West Bank. Site visits

and investigations

in november 2010 have been focused on several road projects in this

area, including latest events at Highway 443. Moreover indepth

research

is ongoing regarding the CityPass project, the construction of a

tramway that will connect the centre of West Jerusalem to settlements

in the

north of East Jerusalem. Please, check our Report here...

While

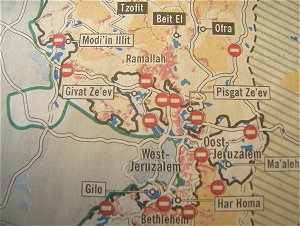

at negotiation tables and Western TV desks opportunities are discussed

for less or no new settlements in the West Bank, a comprehensive car-infrastructure

has been created in the very same area. This infrastructure provides

permanent links between the West Bank and Israel. Without this road

network in 'occupied territory' the policy of settlements would simply

be impossible. In reality, the roads support a military-based control

by Israel on Palestine territory.

Rob van der Bijl and Liesbeth Sluiter investigate these roads. They perform an investigation by means of photography, journalism and mapping the logistic and psychological reality of the West Bank Infrastructure. Their story will illustrate their planned 'car map'. This map is used to depict precisely and profoundly the logistics of Apartheid. In addition, images and stories will be compiled of daily commuters, workers and all the other people who use the roads whether they want to or not, particularly those who are doomed to survive at shoulders and edges of the remaining land.

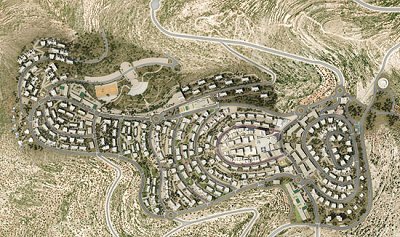

The project started in 2004. Lack of finances forced us to slow down the pace of our activities. However, at the end of 2008 we resumed our work. In November 2010 we made site visits in the region of Jerusalem. Long quote from Yourmiddleeast.com Rawabi, Arabic for hills, is a project that seems impossible to skeptics and optimists alike. Even today, the fact that this is happening seems to astonish some. “Rawabi: is it real or is it a mirage?” asked BBC Arabic in a recent broadcast. But it is very real, proven by the six cameras that constantly update in real time on the development’s website.

Spearheaded by Palestinian-American businessman Bashar Masri, Rawabi stands today only about a year away from the projected first building completions. Masri’s company Massar International funds the project in partnership with the Qatari company Diar. The planned buildings are sleek and polished; they line the hillside in perfect rows. “Rawabi is more than a place to live, it is a way of living,” says the slightly mechanical female voice behind the promotional video. Five neighborhoods surround the heart of the city, which ad campaigns promise will be a bustling commercial district. Complete with industry, health services, schools, and a police station, there will be no need for the future inhabitants to ever leave. Rawabi is a slice of the American dream that has been placed in the middle of Palestine. Not all would agree that this is a good thing, and the project has sustained criticism from some Palestinians as well as violence from the nearby Israeli settlers. The most salient criticism of the project is that it strengthens the Palestinian Authority, a body that grows increasingly unpopular by the day in the Occupied Territories. Rawabi is built in Area A, the rare pieces of land that are under complete PA authority. The city would fit perfectly into Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s strategy of “ending the Occupation, despite the Occupation,” a euphemism for economic development supported with little political action. Masri is aware of the criticism, but insists that the planned city reflects the local culture in both aesthetic and practical ways. “Just to give you a few examples, we knew that Rawabi should be structured around the traditional ‘hai’ neighborhood system that is all across places in Palestine, where neighbors know each other and can gather,” he said in an interview with Green Prophet. “This project is not motivated by politics, it is motivated by our right to be here. It is our right to build on our land wherever we wish.” Economically speaking, it would be much more profitable for him to pursue business initiatives in other parts of the globe, but to him, “Palestine is home.” In the projections, the hills surrounding Rawabi are significantly greener. Every year from now until completion, 15,000 indigenous trees will be planted. In some cases, trees planted by the Jewish National Fund were replaced with local flora. The entire city envisions a greener way of living. According to the developers, “Rawabi will prove that Palestinians are capable of protecting the environment, and will do so better than the residents of the settlements.” According to Masri, finding people to live in Rawabi will not be an issue, since there are so many Palestinians crowded into the existing cities and town. Price will also not be an impediment, as the apartments have been purposefully aimed at middle class Palestinians. Mortgage plans have people paying off their loans at $500-700 a month, similar to the price of renting a flat in Ramallah. The Palestinian economy has been crippled by strict trade restrictions, a series of military checkpoints, and ongoing segregation of their land. In this sense, Rawabi will be able to alleviate some pains. Underemployment and unemployment are two of the Palestinian economy’s most pressing issues to date. The largest private sector development to ever take place in the West Bank, the new city will create 10,000 construction jobs and 4,000 permanent jobs afterwards. For

now, the developers have their fingers crossed, hoping that politics

doesn’t derail their fragile venture. EU

report: Israel policy in West Bank endangers two-state solution The

EU has decided to pursue a series of steps which may undermine Israel's

control of Area C in the West Bank, an official EU document suggests.

The document, titled "Area C and Palestinian state building,"

states that Europe will support road, water, infrastructure, municipal,

educational and medical projects in the area, in order to "support

the Palestinian people and help maintain their presence (in the area)"

(Ynet). Palestinians

irate over new Jerusalem light rail - Jerusalem’s light rail

starts test runs this spring, with its sleek silver cars gliding across

the city and promising to relieve the perpetual congestion. But Palestinians

see no reason to celebrate. "Israel’s

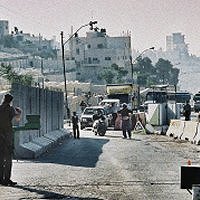

Supreme Court ruled on Tuesday (RVDB: December 26, 2009) that a major

access highway to Jerusalem (RVDB: Highway 443) running through the

occupied West Bank could no longer be closed to most Palestinian traffic.

... In a 2-to-1 decision, the court said the military overstepped

its authority when it closed the road to non-Israeli cars in 2002,

at the height of the second Palestinian uprising. The justices gave

the military five months to come up with another means of ensuring

the security of Israelis that permitted broad Palestinian use of the

road. ... Limor Yehuda, the lawyer who argued the case for the civil

rights group, said she hoped the court would apply the ruling to all

segregated roads in the West Bank to end the dual system there." "Each

time I drive out of Jerusalem into the West Bank, it strikes me: The

hills are changing. Israeli settlements are redrawing the landscape-daily,

insistently. While governments change, while diplomatic conversations

murmur on and stop and begin again, the bulldozers and cranes continue

their work. References Gershom Gorenberg; The Accidental Empire: Israel and the Birth of the Settlements, 1967-1977. New York: Times Books, 2006. Jeff Halper; Obstacles to Peace. A re-framing of the Palestinian - Israeli conflict. Jerusalem: ICAHD & PalMap, Second Edition, February 2004. Malkit Shoshan; Atlas of the Conflict Israel - Palestine. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2010. Rob Van

der Bijl; Een Strategie van Scheidend Asfalt. In: Blauwe Kamer

- Landschapsarchitectuur en Stedenbouw. Februari 2011, nr.1, pp.26-35.

(Including pictures by Liesbeth Sluiter) Karolien Van Dyck; Openbaar vervoer en politieke controle: een empirische studie van het citypass project op de westelijke Jordaanoever. Universiteit van Gent, 2008-2009. Eyal

Weizman; Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of Occupation.

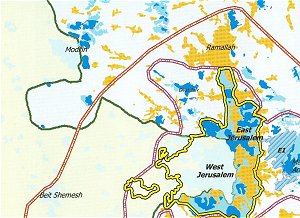

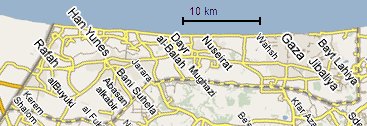

OpenDemocracy Ltd., 2007. Background A reliable

estimate of the area's size is crucial for a good understanding of

the infrastructural conditions. Therefore, with the aid of Google

Maps, we made a series of maps (same scale, same size) in order to

compare the area of Jerusalem/Tel Aviv with respectively the Gaza

strip and coastal zones of Holland and Los Angeles.

In November 2010 Rob van der Bijl and Liesbeth Sluiter made site visits in the region of Jerusalem. They examined the three main targets of their research: Road 443, East Ring Road and CityPass.

This report offers a first impression only. The results of our research are and will be elaborated in forthcoming publications. All pictures by Liesbeth Sluiter. Special thanks to Jan de Jong.

Westoever

Infrastructuur Infrastructuur, in het bijzonder autowegen vormen de condities voor ruimtelijke en sociale segregatie op de Palestijnse Westoever. Rob van der Bijl (stedebouwkundige) en Liesbeth Sluiter (fotograaf) onderzoeken sinds 2004 deze infrastructuur. Zij stellen kaarten, beelden en verhalen samen van de regio Jeruzalem, die ze binnen de Westoever als een sleutelgebied beschouwen. Locatiebezoeken en onderzoek in november 2010 zijn gericht geweest op diverse wegprojecten in het gebied van Jeruzalem, inclusief recente gebeurtenissen rond Highway 443. Bovendien is diepgaand onderzoek lopende naar het CityPass-project, de bouw van een tramlijn die het centrum van West-Jeruzalem zal verbinden met nederzettingen in het noorden van Oost-Jeruzalem. Onze resultaten zijn en zullen in de loop van 2011 worden gepubliceerd in diverse media. Download hier... ons eerste artikel: Een Strategie van Scheidend Asfalt. (In: Blauwe Kamer, februari 2011). Zie ook ons eerdere verslag (november 2010) hier... Helaas

is de situatie sinds ons veldwerk in 2010 in het geheel niet verbeterd.

Januari 2016 roept VN Secretaris-Generaal Ban Ki-moon op tot wijziging

van het beleid. Hij is erg ongerust over de Israëlische aankondiging

om 370 'acres' op de Westoever, ten zuiden van Jericho,

als zogenaamd “State

land” te bestempelen. In dit verband is door de VN

de volgende verklaring uitgebracht: "The

Secretary-General is deeply concerned about reports of the Israeli

Government authorizing the declaration of 370 acres in the West

Bank, south of Jericho, as so-called “State land”.

If implemented, this declaration would constitute the largest land

appropriation by Israel in the West Bank since August 2014.

Terwijl

aan onderhandelingstafels en West-Europese TV-desks de mogelijkheden

van minder of veel minder, of geen nieuwe nederzettingen werd besproken,

is op de Westoever ('West Bank') een auto-infrastructuur gerealiseerd

die het gebied op duurzame wijze koppelt aan het Israëlisch territorium.

Zonder het autowegstelsel in 'bezet gebied' is de nederzettingenpolitiek

simpelweg ondenkbaar. De autowegen maken de fysieke controle van de

Israëli's op het Palestijns gebied pas goed mogelijk.

Rob van der Bijl en Liesbeth Sluiter willen deze logistiek op journalistieke wijze onderzoeken, fotograferen, en letterlijk in kaart brengen. Hun verhaal zal de illustratie vormen van een door hen te vervaardigen 'autokaart'. Hun kaart zal precies en indringend de logistiek van Apartheid in beeld brengen. Daar omheen zullen zij de beelden en de verhalen draperen van de bouwers en van de dagelijkse gebruikers, en vooral van degenen die soms tegen wil en dank van die wegen gebruik maken, maar nog veel vaker gedoemd zijn te overleven in de berm of het resterend land.

Het project is gestart in 2004. De voortgang is door gebrek aan financiële middelen bescheiden geweest, maar eind 2008 hebben we de werkzaamheden weer opgepakt. In november 2010 is veldwerk in Israël uitgevoerd. Rawabi, Arabic for hills, is a project that seems impossible to skeptics and optimists alike. Even today, the fact that this is happening seems to astonish some. “Rawabi: is it real or is it a mirage?” asked BBC Arabic in a recent broadcast. But it is very real, proven by the six cameras that constantly update in real time on the development’s website.

Spearheaded by Palestinian-American businessman Bashar Masri, Rawabi stands today only about a year away from the projected first building completions. Masri’s company Massar International funds the project in partnership with the Qatari company Diar. The planned buildings are sleek and polished; they line the hillside in perfect rows. “Rawabi is more than a place to live, it is a way of living,” says the slightly mechanical female voice behind the promotional video. Five neighborhoods surround the heart of the city, which ad campaigns promise will be a bustling commercial district. Complete with industry, health services, schools, and a police station, there will be no need for the future inhabitants to ever leave. Rawabi is a slice of the American dream that has been placed in the middle of Palestine. Not all would agree that this is a good thing, and the project has sustained criticism from some Palestinians as well as violence from the nearby Israeli settlers. The most salient criticism of the project is that it strengthens the Palestinian Authority, a body that grows increasingly unpopular by the day in the Occupied Territories. Rawabi is built in Area A, the rare pieces of land that are under complete PA authority. The city would fit perfectly into Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s strategy of “ending the Occupation, despite the Occupation,” a euphemism for economic development supported with little political action. Masri is aware of the criticism, but insists that the planned city reflects the local culture in both aesthetic and practical ways. “Just to give you a few examples, we knew that Rawabi should be structured around the traditional ‘hai’ neighborhood system that is all across places in Palestine, where neighbors know each other and can gather,” he said in an interview with Green Prophet. “This project is not motivated by politics, it is motivated by our right to be here. It is our right to build on our land wherever we wish.” Economically speaking, it would be much more profitable for him to pursue business initiatives in other parts of the globe, but to him, “Palestine is home.” In the projections, the hills surrounding Rawabi are significantly greener. Every year from now until completion, 15,000 indigenous trees will be planted. In some cases, trees planted by the Jewish National Fund were replaced with local flora. The entire city envisions a greener way of living. According to the developers, “Rawabi will prove that Palestinians are capable of protecting the environment, and will do so better than the residents of the settlements.” According to Masri, finding people to live in Rawabi will not be an issue, since there are so many Palestinians crowded into the existing cities and town. Price will also not be an impediment, as the apartments have been purposefully aimed at middle class Palestinians. Mortgage plans have people paying off their loans at $500-700 a month, similar to the price of renting a flat in Ramallah. The Palestinian economy has been crippled by strict trade restrictions, a series of military checkpoints, and ongoing segregation of their land. In this sense, Rawabi will be able to alleviate some pains. Underemployment and unemployment are two of the Palestinian economy’s most pressing issues to date. The largest private sector development to ever take place in the West Bank, the new city will create 10,000 construction jobs and 4,000 permanent jobs afterwards. For

now, the developers have their fingers crossed, hoping that politics

doesn’t derail their fragile venture. EU

report: Israel policy in West Bank endangers two-state solution The

EU has decided to pursue a series of steps which may undermine Israel's

control of Area C in the West Bank, an official EU document suggests.

The document, titled "Area C and Palestinian state building,"

states that Europe will support road, water, infrastructure, municipal,

educational and medical projects in the area, in order to "support

the Palestinian people and help maintain their presence (in the area)"

(Ynet). Palestinians

irate over new Jerusalem light rail - Jerusalem’s light rail

starts test runs this spring, with its sleek silver cars gliding across

the city and promising to relieve the perpetual congestion. But Palestinians

see no reason to celebrate. "Palestijnen

mogen na zeven jaar weer gebruik maken van een snelweg die door de

bezette Westelijke Jordaanoever loopt. Het algehele verbod op Palestijns

verkeer voor snelweg 443 is door het Israëlische hooggerechtshof

onrechtmatig verklaard. De vierbaansweg is de kortste route tussen

Tel Aviv en Jeruzalem; 28 kilometer ervan loopt over Palestijns grondgebied.

Referenties Jeff Halper; Obstacles to Peace. A re-framing of the Palestinian - Israeli conflict. Jerusalem: ICAHD & PalMap, Second Edition, February 2004. Malkit Shoshan; Atlas of the Conflict Israel - Palestine. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2010. Rob van

der Bijl; Een Strategie van Scheidend Asfalt. In: Blauwe Kamer

- Landschapsarchitectuur en Stedenbouw, februari 2011, nr.1, pp.26-35.

(Inclusief foto's van Liesbeth Sluiter) Karolien Van Dyck; Openbaar vervoer en politieke controle: een empirische studie van het citypass project op de westelijke Jordaanoever. Universiteit van Gent, 2008-2009. Eyal Weizman; Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of Occupation. OpenDemocracy Ltd., 2007. Achtergrond Voor

een goed begrip van de infrastructurele condities is een reëel

besef van de gebiedsgrootte cruciaal. Als achtergrond is hieronder

met behulp van Google Maps daarom een vergelijking gemaakt tussen

het gebied van Jeruzalem/Tel Aviv met achtereenvolgens de Gaza-strook

en de kusten van respectievelijk de Randstad en Los Angeles.

In november 2010 hebben Rob van der Bijl en Liesbeth Sluiter lokatiebezoeken gemaakt in de regio van Jeruzalem. Ze hebben toen de drie belangrijkste doelen van hun onderzoek verkend: Road 443, East Ring Road en CityPass.

Dit verslag biedt slechts een eerste indruk. De resultaten van ons onderzoek zijn en zullen worden uitgewerkt. Alle foto's door Liesbeth Sluiter. Speciale dank aan Jan de Jong. Zie verder:

|